Where Memory Lives: Exploring Identity and Resilience in Cyprus

Dr. Mihaela Gligor, researcher at the “George Barițiu” History Institute of the Romanian Academy, spent two weeks at the “Saint Epiphanios” Cultural Academy in Ayia Napa through her RESILIENCE Transnational Access (TNA) Fellowship. Her project focused on cultural memory, identity, and migration, which are topics that found a compelling context in Cyprus, a country marked by displacement, division, and deep-rooted religious traditions. We asked her about her experience:

What motivated you to apply for a RESILIENCE TNA Fellowship, and why in Cyprus and at the “Saint Epiphanios” Cultural Academy?

I’m always looking for new academic challenges. When I saw the TNA Call, I thought to explore cultural memory and religious diversity as a constant challenge for European society, especially in relation to migration. Cyprus impressed me during a previous visit with its diversity and openness. It’s home not only to Cypriots but also to communities who fled conflict zones. I wanted to learn more about its history and people, and the “Saint Epiphanios” Cultural Academy seemed the perfect place to do so.

The RESILIENCE TNA Fellowship gave me something I could not have achieved on my own: direct access to local experts, clergy, and community members, as well as the Academy’s resources and library. This support allowed me to move beyond theoretical research and engage with living practices of memory and identity. It opened doors to conversations and experiences that enriched my understanding and will significantly shape my future work.

How did your stay at the Academy deepen your understanding of Cyprus?

It was a transformative experience. I met people who live their faith as a tool for helping others. The “Saint Epiphanios” Cultural Academy’s programs and the Ayia Napa parish showed genuine openness toward different cultures and a strong commitment to social support. I also discovered Cyprus’s traumatic history of forced internal migration—something I hadn’t realized as a tourist. This experience helped me understand how displacement shapes identity and memory. The Academy addresses these issues through publications, exhibitions, and educational activities, making it a vibrant hub for cultural dialogue.

How did the Cypriot context engage your research themes of cultural memory, identity, and migration?

Cyprus is a country with borders inside its territory and a recent traumatic past, yet it proudly reaffirms its Christian heritage. Memory practices—texts, images, rituals—shape community identity, and I saw this in the Academy’s work. The medieval monastery housing the Academy and its library is not just a historical site but a living space where traditions are preserved and shared.

What impressed me most was the parish’s ability to create a unique community where immigrants are respected, maintain their identity, and still belong. People from different parts of the world, sometimes of different religions, were welcomed and supported. What politics couldn’t solve, this parish could. This experience gave me concrete examples of resilience and coexistence that will inform my future research on belonging and home.

What insights emerged from your interactions with local communities?

Cyprus is an ideal place to study coexistence in an entangled Europe. Conversations with clergy and locals revealed how faith and cultural identity foster resilience and belonging. Despite its complex history, Cyprus welcomes everyone and encourages active participation in society, a powerful lesson for creating a better future.

I left with a deeper understanding of how cultural memory operates in practice: through rituals, shared spaces, and acts of solidarity. These insights will help me address key concepts of identity and belonging in my academic work.

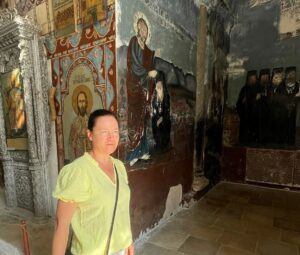

Photo: Inside of the St Barnabas Monastery near Salamis in Northern Cyprus.

How did Cyprus’ history of internal migration and division influence your understanding of belonging and resilience?

Concepts such as cultural identity, belonging, immigration, and exile are deeply interconnected, and Cyprus provided fertile ground to explore them. Before my fellowship, I was not fully aware of the island’s complex history of displacement and refugeehood. Experiencing this firsthand changed my perspective. When I crossed into northern Cyprus, I observed striking cultural differences and transformations of places of worship, visible signs of how identity and memory adapt under political and social pressures. These changes raise difficult questions: How do religious conversions relate to integration and belonging? What happens when someone is forced to leave their culture behind? Where is home, and what does it truly mean?

One story illustrates this powerfully. A woman displaced from Varosha in 1974 told me, “Home is where your family is.” Her family fled with nothing, lived in tents, and rebuilt their lives from scratch. For years, they hoped to return, but eventually realized that home is not a physical house, it is togetherness. Her parents never saw their home again. Even after Varosha was partially opened to visitors, she was not allowed to enter her family’s house, which remains inaccessible.

Her story deeply impressed me. It is sad, but also profoundly meaningful because it speaks to resilience and the human capacity to endure and start over. It reframed my understanding of home as a dynamic concept, shifting from a place to a feeling, from geography to relationships. This insight will strongly influence my future research on belonging and identity in contexts of migration and displacement.

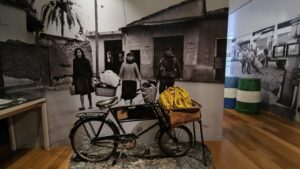

Photo: Exhibition at the Leventis Municipal Museum in Nicosia, which vividly depicts the 5,000-year development of the capital of Cyprus.

What advice would you give future RESILIENCE TNA fellows?

For anyone interested in Cyprus’s history and cultural dialogue, the “Saint Epiphanios” Cultural Academy is the perfect place. It offers not only access to resources but also opportunities to engage with people who live these traditions every day. My advice is to come with curiosity and openness: speak with locals, attend parish activities, and explore places of memory. These experiences will enrich your research far beyond what you can find in books.

The Cyprus I knew as a tourist was beautiful, but the Cyprus I discovered during my fellowship was profound and full of meaning. I am grateful to the Academy, the Ayia Napa parish, and the RESILIENCE TNA Fellowship for making this possible.

***

Thank you for sharing such valuable insights into your experiences in Cyprus, dear Mihaela Gligor. We wish you great success as you continue your research journey.